The choice between one and three arbitrators is an important decision parties do not always pay attention to when drafting arbitration clauses, or even once a dispute has arisen. The choice of who will sit on the panel, including whether it will be a sole arbitrator or a three-member tribunal, is one of the most important decisions in the arbitration. It can also have a significant impact on the efficiency of the arbitration proceedings and their overall cost.

Parties are allowed and quite frequently specify the number of arbitrators in their arbitration clauses. This is one of the key elements of party autonomy. Parties are not always entirely free to determine any number of arbitrators, however, as many national laws and procedural rules require the number to be uneven in order to avoid split decisions. Most procedural rules also provide that the parties are free to choose to have one or three arbitrators, but the number has to be uneven. [1] If the parties wish, however, they can also leave it open to opt for one or three arbitrators once a dispute has arisen. In the absence of the parties’ agreement, the number of arbitrators will be determined by the appointing authority and/or the arbitral institution.

Whether it is always a wise decision to specify the number of arbitrators in an arbitration clause is debatable. Sometimes it may be worthwhile leaving the question open to be decided at later stages once a dispute has arisen, especially for large contracts. Various factors should be taken into consideration when opting for a sole arbitrator or a three-member arbitral tribunal, especially the amount in dispute and the costs of the arbitral tribunal, which may vary significantly.

Having a dispute decided by a sole arbitrator has several advantages, especially in lower-value contracts where the amount in dispute is not that high, or the parties prefer to save on dispute resolution costs.

The costs of arbitration are significantly lower in case of a single arbitrator when compared to a three-person tribunal. It is not difficult to comprehend that paying the professional fees of three arbitrators will be greater than paying the professional fees of one arbitrator. It is a certainty when appointing a sole arbitrator that arbitration costs will be lower.

For instance, the total ICC arbitration costs with an amount in dispute of USD 5 million is estimated at USD 132,349 with a sole arbitrator whereas, in the case of three arbitrators, to rule on the same dispute, the parties would have to pay the ICC approximately USD 307,017. [2] The difference in overall costs is substantial.

A common tactic, even in relatively small disputes, is for one party to insist on a three-member arbitral tribunal in order to drive up costs, especially when the parties do not have equal litigation budgets at their disposal. More than one arbitration has been withdrawn due to tactics by one party, typically the respondent, designed to increase the costs of arbitration, in the hope that the arbitration will be abandoned.

Sole arbitrators also tend to resolve disputes more efficiently, although this is not always be the case. Three arbitrators have to discuss each decision between themselves, coordinate their calendars, and consult with each other throughout arbitration proceedings, especially while drafting procedural orders and the final award. Sole arbitrators, on the other hand, can easily streamline the process on their own and focus solely on drafting the award without needing to consult with other members. Statistics also confirm that sole arbitrators typically issue their awards within less time than a three-member tribunal, although the difference is not that substantial (see The Duration of Arbitration).

Appointing a sole arbitrator can have certain disadvantages, however. In certain cases, a three-member tribunal is considered a safer option, especially in complex cases where the amount in dispute is substantial.

First, having three arbitrators in theory reduces the risk of issuing poor decisions and diminishes errors and mistakes. Arbitrators are human and they are not infallible. The more complex a case is, the more chances of mistakes there are. Having six pairs of eyes instead of two, and a careful scrutiny of the award, ideally by all three members, naturally reduces the risk of errors. Considering that there is normally no possibility of an appeal, this is even more important in international arbitration than in litigation. Reducing errors is also important in order to avoid problems with enforcement and/or annulment at post-arbitration stages.

Second, three arbitrators naturally engage in discussions, offer different perspectives, and assist each other with their understanding of complex issues, which can be beneficial for more complex disputes. There is also a benefit to appointing three members with diverse legal and cultural backgrounds and/or experience in specific industries and sectors. It can further be helpful to have members of the tribunal who speak a specific language and have specialized knowledge of a certain legal system.

Finally, there is also a general perception, especially amongst the parties and their in-house counsel, that having three arbitrators leads to greater neutrality of the panel. It is normal practice that each party gets to appoint one arbitrator, which, in certain parties’ view, creates a more “balanced” tribunal. The parties also generally perceive it to be safer to have three members rather than putting everything in the hands of one person. [3]

Should the parties therefore specify the number of arbitrators in their arbitration clauses from the outset, or leave it open to be decided once a dispute has arisen? The simple answer is – except for small contracts, it is generally prudent to leave the issue open.

If the parties search for model arbitration clauses recommended by various institutions this is not that clear. Most arbitral institutions recommend to the parties to specify that the dispute shall be resolved by one or more arbitrators. The ICC model arbitration clause reads:

All disputes arising out of or in connection with the present contract shall be finally settled under the Rules of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce by one or more arbitrators appointed in accordance with the said Rules.

The SCC similarly recommends to the parties to specify that the arbitral tribunal shall be composed of three arbitrators or a sole arbitrator:

Any dispute, controversy or claim arising out of or in connection with this contract, or the breach, termination or invalidity thereof, shall be finally settled by arbitration in accordance with the Arbitration Rules of the SCC Arbitration Institute.

The arbitral tribunal shall be composed of three arbitrators/a sole arbitrator.

The seat of arbitration shall be […].

The language to be used in the arbitral proceedings shall be […].

This contract shall be governed by the substantive law of […].

The SIAC also recommends that, in drawing up international contracts, the parties should specify the number of arbitrators, which should be uneven:

Any dispute arising out of or in connection with this contract, including any question regarding its existence, validity or termination, shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration administered by the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (“SIAC”) in accordance with the Arbitration Rules of the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (“SIAC Rules”) for the time being in force, which rules are deemed to be incorporated by reference in this clause.

The seat of the arbitration shall be [Singapore].*

The Tribunal shall consist of _________________** arbitrator(s).

The language of the arbitration shall be ________________.

The same is true for the LCIA, which recommends the following arbitration clause:

Any dispute arising out of or in connection with this contract, including any question regarding its existence, validity or termination, shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration under the LCIA Rules, which Rules are deemed to be incorporated by reference into this clause.

The number of arbitrators shall be [one/three].

The seat, or legal place, of arbitration shall be [City and/or Country].

The language to be used in the arbitral proceedings shall be [ ].

The governing law of the contract shall be the substantive law of [ ].

What happens in case the parties are unable to agree on the number of arbitrators (i.e., one party insists on a sole arbitrator and the other on three arbitrators)? In such a case, the decision is to be made by the appointing authority and/or arbitral institution, which usually makes its decision based on the complexity of the case and the amount in dispute.

The ICC, for instance, leaves it to the ICC Court to determine the size of the tribunal. Article 12(2) of the ICC Rules creates a presumption in favour of a sole arbitrator. This is, however, only a presumption and it is up to the ICC Court to make the ultimate decision. [4] The Secretariat’s Guide to ICC Arbitration lists several criteria that the ICC Court takes into account, inter alia: [5]

The UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, in contrast with the ICC Rules, lean toward the appointment of three arbitrators as a rule, unless the parties have agreed otherwise:

Article 7 1. If the parties have not previously agreed on the number of arbitrators, and if within 30 days after the receipt by the respondent of the notice of arbitration the parties have not agreed that there shall be only one arbitrator, three arbitrators shall be appointed.

Article 7.2 of the UNCITRAL Rules provides that, if the other party has not responded to the proposal for an appointment of a sole arbitrator and the other party has failed to appoint a second arbitrator, the appointing authority may nevertheless appoint a sole arbitrator pursuant to the procedure as provided in Article 8, if it determines that, in view of the circumstances of the case, this would be appropriate:

Article 7.2. Notwithstanding paragraph 1, if no other parties have responded to a party’s proposal to appoint a sole arbitrator within the time limit provided for in paragraph 1 and the party or parties concerned have failed to appoint a second arbitrator in accordance with article 9 or 10, the appointing authority may, at the request of a party, appoint a sole arbitrator pursuant to the procedure provided for in article 8, paragraph 2, if it determines that, in view of the circumstances of the case, this is more appropriate.

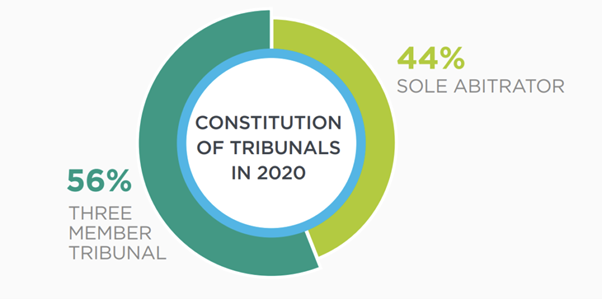

Statics reveal that, in practice, the vast majority of parties manage to agree on the number of arbitrators, with a slightly higher preference for three members as opposed to sole arbitrators. ICC Caseload statistics for 2020 demonstrate that, in 2020, the vast majority of parties agreed on the number of arbitrators (87%), whereas they opted for a three-member tribunal in 62% of the cases, and a sole arbitrator in 38%. In the remaining 13% of cases, the ICC Court fixed the number of arbitrators. As a result, in 2020, 56% of the total number of ICC cases were resolved by a three-member tribunal and 44% by a sole arbitrator:

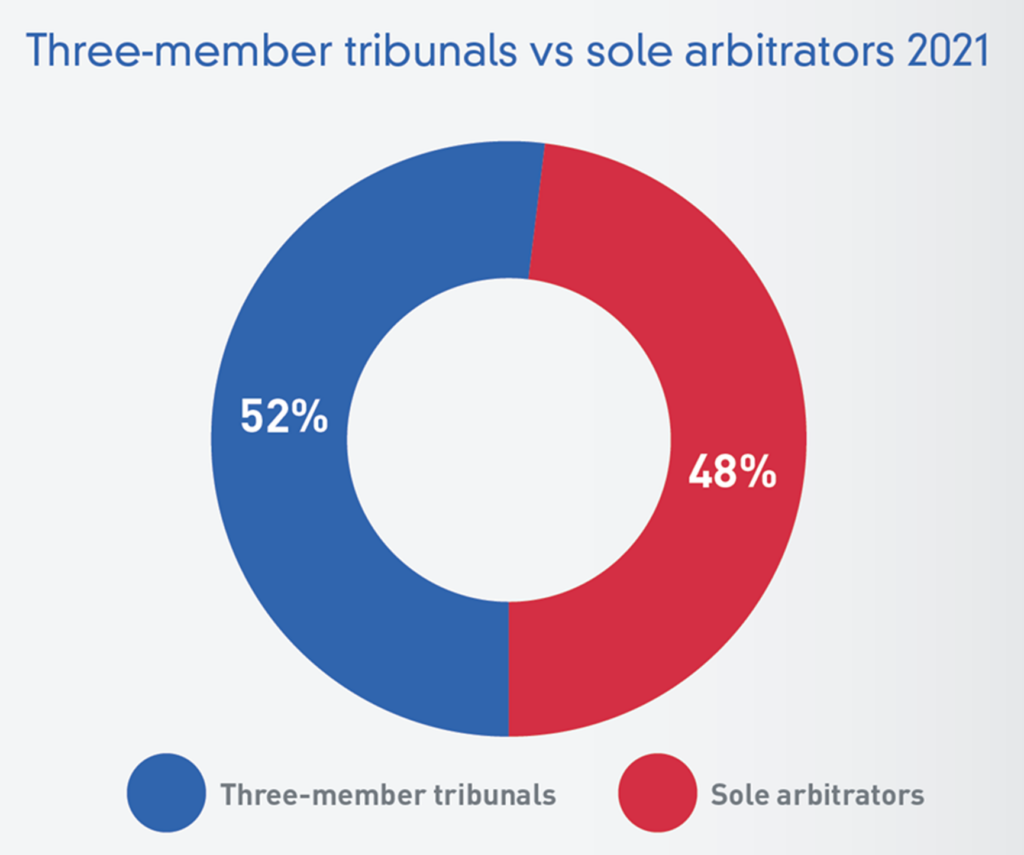

The LCIA Caseload statistics for 2021 reveal that, in 2021, 52% of tribunals were three-member tribunals, and 48% were sole arbitrator tribunals:

versus Three Arbitrators" width="602" height="503" />

versus Three Arbitrators" width="602" height="503" />

The SCC statistics also show similar results. In 2021, 58% of the 103 cases commenced under the SCC Arbitration Rules were decided by a three-member tribunal, whereas 36% of the cases were decided by a sole arbitrator.

Statistics accordingly show that there is still a slight preference towards having a three-member arbitral tribunal, although having a sole arbitrator is necessarily less costly.

[1] 2021 ICC Rules, Article 12(1); 2017 SCC Rules, Article 16 (1); 2016 SIAC Rules, Rules 10-11.

[3] M.A. Burgos, “The Fear of a Sole Arbitrator”, Kluwer Arbitration Blog, 7 August 2018.

[4] J. Fry, S. Greenberg and F. Mazza, The Secretariat’s Guide to ICC Arbitration, ICC 2012, para. 3-439.

[5] J. Fry, S. Greenberg and F. Mazza, The Secretariat’s Guide to ICC Arbitration, ICC 2012, paras. 3-438 – 3-440.